When shipping medical equipment overseas it’s easy to overlook and get caught out by obstructive regulations. In previous articles we’ve discussed some of the problems that can arise when a shipment arrives at its destination. In this article we’ll look at some issues that can prevent the shipment even leaving Australia or failing to arrive, if not dealt with properly.

.

Donated medical equipment shipped in a container is usually packed into the container as is, without any additional protection. However, more fragile items may need to be securely packed, particularly if they are to be shipped as less-than-container-load (LCL) cargo. If the equipment is to be packed into a wooden box or crate, it’s important to use the right timber. All wooden packing material, including pallets, used for export must meet the requirements of the International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPM). In the case of timber used for international shipping purposes the standard is ISPM15. It applies to all wood more than 6mm thick and requires it to be treated against pests, meet bark tolerance requirements and be appropriately marked as shown at image 1.

All professional packers for export will know about this requirement, but anyone less may not. If unsuitable timber is used and it is not detected before leaving Australia, the cases may be destroyed on arrival overseas or be refused entry. At very least they will be sent for treatment, risking damage to the contents. In summary, always specify ISPM15 timber when packing for export. For more information go to https://www.agriculture.gov.au/export/from-australia/wood-packaging/faq-ispm15#what-is-ispm-15

Insurance – who needs it?

Most donated, used equipment is shipped uninsured because shippers don’t want to pay premiums for goods of little or no commercial value. Insurance for second-hand goods is difficult to get anyway, and if it is obtained it tends to negate the low-value declaration made on shipping documents to help the receiver avoid customs duty and taxes. However, if new or high-value used goods are being shipped it could be an expensive mistake not to insure them. Enquire about premiums with your freight forwarder to make an informed decision and then specify “insurance required” on your shipping instructions if appropriate.

Container safety versus culpability

There is a horrifying Youtube that can be found on the internet where a container is being lifted by a crane and about to be swung onto the ship, when the floor of the container suddenly bursts open and a load of concrete slabs crashes onto the wharf below. Had anyone been standing underneath they would have been killed instantly. That container somehow slipped through the safety checks and you wouldn’t want to be the person responsible for it. If you’re going to buy your own used container you must make sure that it meets the standard for export. This is governed by the International Convention for Safe Containers. Not any old container will do as those sold for storage, for example, may not be structurally sound for shipping purposes. So when buying a used container specify that it will be used for export shipping purposes and ensure that it has a valid CSC plate and certificate. The plate looks something like image 2 and is usually attached to the left door.

Agonising over air freight

DAISI doesn’t normally use air freight but those who do will know that since 1 March 2019 all air freight exported from Australia must be x-ray screened before it can be loaded onto the aircraft. This procedure, known as piece level screening, was introduced in response to heightened security concerns. Freight is classified as either homogenous – where all the items in a carton are exactly the same and uniform in every respect when viewed on an x-ray monitor – or non-homogenous where cartons contain mixed goods of varying shapes and sizes. If you do use air freight on occasion and are shipping non-homogenous goods, make sure the cartons are supplied loose and not on pallets. The reason for this is that if the security staff are not certain of what they are seeing on the x-ray monitor, they will open the carton for a manual inspection. If the cartons are plastic-wrapped onto a pallet they can’t do this and the whole consignment will be returned to you for resubmission at your expense.

Batteries not included?

Medical devices are replete with lithium batteries – lithium ion and lithium metal – which are among the most contentious items in the shipping world. On the face of it they are categorised as Class 9 dangerous goods and have been implicated in a number of aircraft and cargo ship fires. However, there are many, many exceptions to the rule which are beyond the scope of this article to describe in detail, but suffice it to say that the final classification of lithium batteries will depend on a number of considerations including the following:

- Are the batteries installed in the equipment?

- If not, are they packed separately with the equipment?

- Are they lithium ion (generally rechargeable) or lithium metal (generally not rechargeable)?

- How many batteries are there in total?

- What is the rating of the batteries in watt hours?

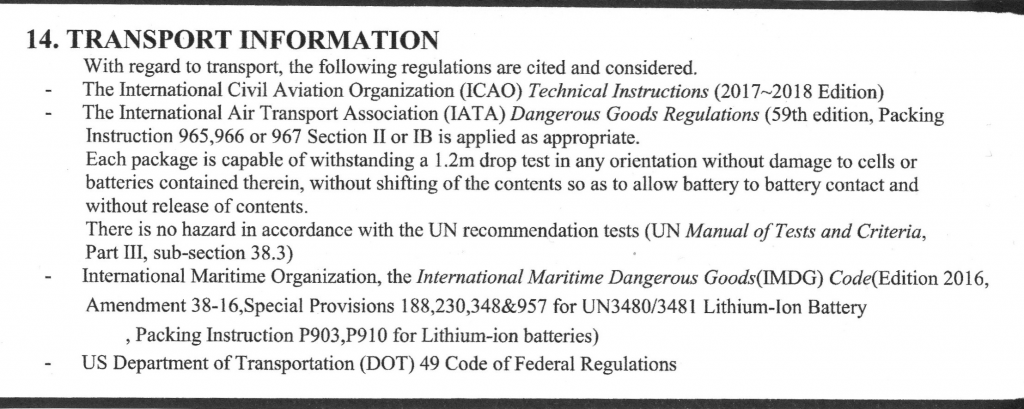

As a very rough rule of thumb, if the batteries are either installed in the device or packed separately with it, are limited in number and have a rating of less than 100 watt hours, they will be an exception to the dangerous goods regulations. However, there is a lot more to it than that so get advice from your freight forwarder as declarations and hazard labels may be required. Note that different rules apply to different transport modes – IATA for air freight and IMDG for sea freight. A good way to make a self-determination is to get hold of a material safety data sheet (MSDS) from the battery supplier and check the Transport section. In the example at image 3 it indicates that the batteries in question will be an exception to the dangerous goods rule so long as certain packing instructions are complied with.

Shipping can be a headache, but it will be a lot easier armed with an awareness of the obstacles and how to overcome them.

Barry Barford is an Associate Member of DAISI and a former Shipping & Logistics Officer.